The acronym (see Tayur’s Eleven for some fun stories) was indeed chosen to match

Edson Arantes do Nascimento, better known by his nickname Pelé (Brazilian Portuguese: [peˈlɛ]), was a Brazilian professional footballer who played as a forward. Widely regarded as one of the greatest players of all time, he was among the most successful and popular sports figures of the 20th century.

The first movie I saw (likely at the Open Air Theater, OAT, at IIT Madras) with him in it was

Escape to Victory (or simply Victory) is a 1981 sports war film directed by John Huston and starring Sylvester Stallone, Michael Caine, Max von Sydow and Pelé. The film is about Allied prisoners of war who are interned in a German prison camp during the Second World War who play an exhibition match of football against a German team.

Talking about movies, and South America, I watched this Argentinian film (at Main Cinema in Minneapolis) a couple days back:

Kill the Jockey (Spanish: El jockey) is a 2024 surrealist neo-noir psychological drama film co-written and directed by Luis Ortega, starring Nahuel Pérez Biscayart alongside Úrsula Corberó and Daniel Giménez Cacho.

Apart from my general interest in Independent an Foreign Films (see Quentin Tarantino), and because I really liked the Oscar winner from many years ago, The Secret in their Eyes, I also wanted to see:

Úrsula Corberó Delgado is a Spanish actress. She gained international recognition for her role as Tokyo in the crime drama series Money Heist (2017–2021). In February 2024, she joined Eddie Redmayne and Lashana Lynch in the series The Day of the Jackal.

Here are some recent streaming series that I have enjoyed.

UK. Dept. Q. Denmark. Secrets We Keep. Sweden. The Glass Dome. Turkey. Graveyard.

US. Sirens. Waterfront. Untamed.

Okay, now to the main topic of the post.

As I have been reading books and articles and biographies related to Political Economy, I wondered:

Is the history of political economy shaped not only by the intellectual rigor and analytic tools of its founders, but also influenced by their personal experiences, including (but not limited to) upbringing, marital life and wealth (or lack thereof)?

Adam Smith, born into a comfortable but not extravagant Scottish family, himself never married (no children and lived with his mother), envisioned capitalism as a potential force for broad progress. His works championed the division of labor and market efficiency, suggesting that growth could yield “universal opulence” that would even benefit the lower classes. Smith largely believed that economic gains, when guided by enlightened self-interest and competitive markets, could be widely shared, and he viewed wealth primarily as a product of productive labor and capital accumulation, not of mere money-hoarding. His own modest lifestyle and focus on the well-being of society colored his optimistic outlook.

Friedrich Engels grew up in the economic elite, as heir to a textile fortune. Unlike most political economists, Engels directly used his wealth to fund political activism and support Marx’s work. Engels’s privileged background, paradoxically, gave him the means to critique capitalism from within, and the social connections to observe industrial capitalism’s realities up close. His role as both (a reluctant) capitalist and revolutionary was highly unusual, shaping a nuanced view of exploitation and class dynamics.

Karl Marx, often beset by financial hardship, interpreted the same forces of accumulation and labor division as engines of exploitation. For him, the capitalist system inherently enriched the bourgeois class while impoverishing the proletariat. Marx’s skepticism of wealth as a unifying social good—and his focus on class conflict—reflected both his personal struggles and his immersion in radical politics. Marx’s deep engagement with ideas of exploitation and alienation was arguably heightened by his experiences at the margins of bourgeois society.

David Ricardo, in sharp contrast, was a self-made millionaire and successful financier before becoming a theorist. His great personal wealth allowed him the freedom to devote himself to intellectual pursuits and political reform. Ricardo’s perspective was pragmatic: he analyzed class interest and rent-seeking behavior, warning that unchecked land rents could choke economic growth. Yet, his affluent status and practical success in markets informed his embrace of free trade and market mechanisms, even as he dissected tensions among landlords, capitalists, and workers.

John Maynard Keynes was born into an intellectual upper-middle-class family, later achieving substantial independent wealth through investing. His insider status among British elites and personal comfort informed his belief that capitalism could and should be reformed through intelligent state intervention. Keynes advocated not for revolution, but for policies to stabilize markets and preserve prosperity—a vision aligned with his experience of privilege coupled with a sense of public responsibility.

Friedrich Hayek, son of a prosperous Viennese family and a veteran of World War I, emerged as one of the twentieth century’s most influential economists and political philosophers. Deeply influenced by the social upheaval of postwar Austria and the threats posed by totalitarian ideologies, Hayek championed free-market capitalism and warned that even well-intentioned government planning risked eroding personal freedoms. Hayek’s skepticism of state intervention and faith in spontaneous order reflects both his personal experiences and his theoretical convictions.

Josef Schumpeter was born to a prosperous textile manufacturer’s family in Austria-Hungary, and enjoyed early financial comfort. However, his father died when Josef was four, and the family’s situation became less secure, particularly after his stepfather’s death. Schumpeter faced catastrophic loss of fortune during Austria’s postwar financial collapse, professional disappointment as his contemporaries eclipsed his influence in Europe, and deep personal grief (loss of his second wife and a child). His own experiences with risk, loss, and reinvention helped crystalize this vision of relentless dynamism and instability. He championed the entrepreneur as the engine of economic transformation, likely inspired by both his own business ventures and the tumultuous changes he witnessed in Europe.

Milton Friedman, son of poor immigrants, rose through merit in academia and policy circles. His skepticism of government intervention and defense of free-market solutions reflect both a personal belief in self-reliance and a strong commitment to individual liberty. His modest background did not incline him toward revolutionary redistribution but rather to faith in opportunity and markets.

Karl Polanyi, from a well-educated but not exceptionally wealthy background, witnessed firsthand the disruptive effects of unregulated markets. His analysis of the “great transformation”—the social crises provoked by unrestrained capitalism—was informed by his experience of upheaval in early 20th-century Europe. Polanyi’s work carries a deep skepticism of markets left to their own devices, stemming from observed social dislocation rather than personal affluence or deprivation.

As an Academic Capitalist, I perhaps relate most with David Ricardo, while finding the insights of Karl Polyani thoughtful. I plan to delve in more detail, over the next few months, into the interplay of Capitalism and Democracy, especially as it affects Sustainability (see Capitalism, Sustainability and Democracy), Media (NPR, PBS and GBH, where I was on the Board of Overseers), Tariffs (so Supply Chains), and Academia, among other things, and whether Innovation will indeed find us creative solutions (see Capitalism, Innovation and Democracy).

Moving to here and now.

As many of you know (see An Academic Capitalist View of Life), I am a Charter Member of TiE Pittsburgh (and an LP in their Angel Fund, that is a LP in 412 Venture Fund, that is an investor in many local startups). I also enjoyed being part of TiEBoston during my stay there, especially with the first three cohorts of TieScaleUp inititative (that included social entrepreneurs Liz Powers from ArtLifting and Rupal Patel from VocalID).

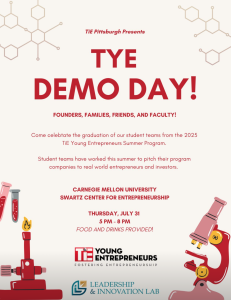

In Minneapolis, it was a treat to meet up with Kingshuk Sinha, for a sumptuous (all-vegetarian, Bengali, home cooked) dinner (thank you Sharmistha), and discuss innovations and challenges in AI, Personalized Care and Mental Health (see The Importance of Being Caring) along with Adam Moen (and his app Avalo). In Pittsburgh, I am looking forward to (TYE, TiE Young Entrepreneurs, on July 31, at Swartz Center for Entrepreneurship, in our office building at Tepper, and hope to see many of you there):

Great article! One quibble: I do not think Engels was a capitalist — he was an heir of a capitalist fortune. He was rebelling against the system his parents became successful with, not himself (at least not directly).

My pushback is: I believe he eventually participated as a partner in his father’s enterprise and so benefited from the payouts and lifestyle that it provided. I agree that he was at best a reluctant Capitalist. Let me see if I can reword that part a bit.